This surprising exhibition from Marcia Lippman, on view at Nailya Alexander Gallery through March 2, is not what it first appears to be. Or rather, its obvious pleasures are not to be enjoyed without some chastening. Although the photographer herself would probably disagree, the show is a bit like a brocade handbag with a blackjack inside. Lippman seems to have surrendered completely to the blandishments of painting, which early on supplied photography its compositional models, display ambitions, and critical language.

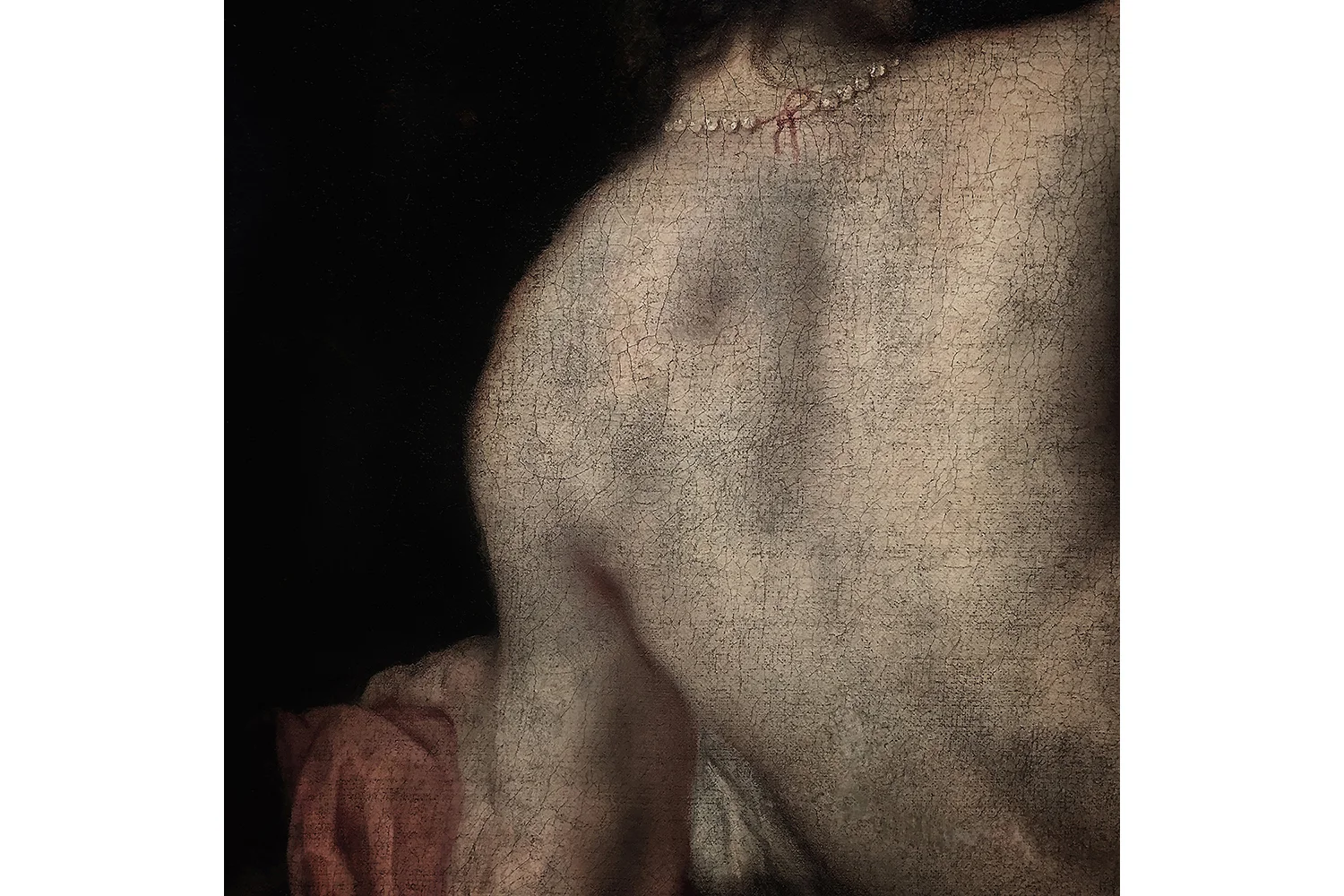

Seduced by the surface effects of European masters from three centuries, Lippman photographed details from paintings that include swatches of gowns, lace ruffs, the sensuous backs of nudes. These virtuoso passages are replete with strokes of the artists’ brush that incarnate the mystery photography can never achieve: the tactile miracle of transformation, as specific gestures become significant wholes. In the age of the cell phone, most of us involved with photography have shot details in museums with a mixture of envy and despair. As it has since the days of Steichen, poor photography, recorder of two dimensions in the real world, must wait on such condescending plenitude.

Except for the cracks. Lippman scans her film negatives and uses software to heighten ever so slightly the appearance of tiny cracks in the surface of the paintings. These and other delicate modifications emphasize the inevitable breakdown of the artist’s materials under the relentless pressure of time. It is in facing the question of time that photography asserts its analytical priority, and Lippman’s project displaces genuflection with introspection. These squares of eternity, of supposedly timeless beauty, are rendered mortal. Lippman’s photographs hold open the process that time itself would seal up, to show us the work of time on pigments, oils, and canvas. This process contests the painters’ gestures – more visible through Lippman’s intervention. In seeming to submit to painting, these photographs triumph over it. Or rather, they render its ultimate pathos (as only photographs can), a pathos intimately bound up with love.

Lyle Rexer, Photograph, March/April 2017